|

|

|

September 1776: Jaws of the Empire | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

From LOSSING’s PICTORIAL FIELD BOOK of the REVOLUTIONARY WAR: (see transcriber’s note)

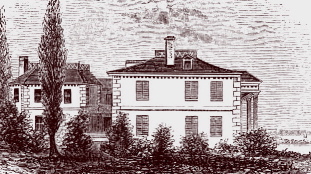

“Washington made the house of Robert Murray, on Murray Hill, his quarters on the fourteenth, and on the fifteenth he was at Mott’s tavern, now the property of Mr. Pentz, near One hundred and Forty-third Street and Eighth Avenue. It was at Murray’s house that Captain Nathan Hale received his secret instructions for the expedition which cost him his life.” |

At a council of war held on the seventh, a majority of officers were in favor of retaining the city; but on the twelfth, another council, with only three dissenting voices (Heath, Spencer, and Clinton), resolved on an evacuation. The movement was immediately commenced, under the general superintendence of Colonel Glover.

The sick were taken to New Jersey, and the public stores were conveyed to Dobbs’s Ferry, twenty miles from the city. The main body of the army moved toward Mount Washingtonand King’s Bridge on the thirteenth, accompanied by a large number of Whigs and their families and effects. A rear-guard of four thousand men, under Putnam, was left in the city, with orders to follow, if necessary, and on the sixteenth Washington made his head-quarters at the deserted mansion of Colonel Roger Morris, on the heights of Harlem River, about ten miles from the city.

Every muscle and implement was now put in vigorous action, and before the British had taken possession of the city the Americans were quite strongly intrenched. At Turtle Bay, Horn’s Hook, Fort Washington and the heights in the vicinity, on the Hudson and Harlem Rivers, and near King’s Bridge, traces of these fortifications may yet be seen.

![]() See Lossings comprehensive description of the FORTIFICATIONS:

See Lossings comprehensive description of the FORTIFICATIONS: ![]()

Large detachments were sent in boats from Hallet’s Point to occupy Buchanan’s and Montressor’s (now Ward’s and Randall’s) Islands, at the mouth of the Harlem River.

Early on Sunday morning the fifteenth [Sept., 1776.], Sir Henry Clinton, with four thousand men, crossed the river in flat bottomed boats from the mouth of Newtown Creek, and landed at Kip’s Bay (foot of Thirty-fourth Street) under cover of a severe cannonade from ten ships of war, which had sailed up and anchored opposite the present House of Refuge, at the foot of Twenty-third Street. 36

Another division, consisting chiefly of Hessians, embarked a little above, and landed near the same place. The brigades of Parsons and Fellows, panic-stricken by the cannonade and the martial array, fled in confusion (many without firing a gun) when the advanced guard of only fifty men landed. Washington, at Harlem, heard the cannonade, leaped into the saddle, and approached Kip’s Bay in time to meet the frightened fugitives. Their generals were trying in vain to rally them, and the commander-in-chief was equally unsuccessful.

Mortified, almost despairing, at this exhibition of cowardice in the face of the enemy, Washington’s feelings mastered his judgment, and casting his chapeau to the ground, and drawing his sword, he spurred toward the enemy, and sought death rather than life. One of his aids caught his bridle-rein and drew him from danger, when reason resumed its power. 37 Unopposed, the British landed in full force, and, after skirmishing in the rear of Kip’s house with the advance of Glover’s brigade, who had reached the scene, they marched almost to the center of the island, and encamped upon the Incleberg, an eminence between the present Fifth and Sixth Avenues and Thirty-fifth and Thirty-eighth Streets. The Americans retreated to Bloomingdale, and Washington sent an express to Putnam in the city, ordering him to evacuate it immediately. Howe, with Clinton, Tryon, and a few others, went to the house of Robert Murray, of Murray Hill, for refreshments and rest. With smiles and pleasant conversation, and a profusion of cake and wine, the good Whig lady detained the gallant Britons almost two hours; quite long enough for the bulk of Putnam’s division of four thousand men to leave the city and escape to the heights of Harlem by the Bloomingdale road, with the loss of only a few soldiers. 38

General Robertson, with a strong force, marched to take possession of the city, and Howe made his head-quarters at the elegant mansion of James Beckman, at Turtle Bay, then deserted by the owner and his family. (39n-deleted here) Before sunset his troops were encamped in a line extending from Horn’s Hook across the island to Bloomingdale. Harlem Plains divided the hostile camps. For seven years, two months, and ten days [Sept. 15, 1776, to Nov. 25, 1783.] from this time, the city of New York remained in possession of the British troops.

HARLEM PLAINS, FROM A ROOF ON MOUNT MORRIS. |

The wearied patriots from the city, drenched by a sudden shower, slept in the open air on the heights of Harlem that night.

Early the next morning [Sept. 16.] intelligence came that a British force, under Brigadier Leslie, was making its way by M‘Gowan’s pass to Harlem Plains. The little garrisons at Mount Morris and Harlem Cove (Manhattanville) confronted them at the mouth of a deep rocky gorge, (40n deleted here) and kept them in partial check until the arrival of re-enforcements. Washington was at Morris’s house, and hearing the firing, rode to his outpost, where the Convent of the Sacred Heart now stands. There he met Colonel Knowlton, of the Connecticut Rangers (Congress’s Own), who had been skirmishing with the advancing foe, and now came for orders. The enemy were about three hundred strong upon the plain, and had a reserve in the woods upon the heights. Knowlton was to hasten with his Rangers, and Major Leitch with three companies of Weedon’s Virginia regiment, to gain the rear of the advance, while a feigned attack was to be made in front. Perceiving this, the enemy rushed forward to gain an advantageous position on the plain, when they were attacked by Knowlton and Leitch on the flank. Re-enforcements now came down from the hills, when the enemy changed front and fell upon the Americans. A short but severe conflict ensued. Three bullets passed through the body of Leitch, and he was borne away. A few moments afterward, Knowlton received a bullet in his head, fell, and was borne off by his sorrowing companions. 41 Yet their men fought bravely, disputing the ground inch by inch as they fell back toward the American camp. The enemy pressed hard upon them, until a part of the Maryland regiments of Colonels Griffiths and Richardson re-enforced the patriots. The British were driven back across the plain, when Washington, fearing an ambush, ordered a retreat. The loss of the Americans was inconsiderable in numbers; that of the British was eighteen killed and about ninety wounded. This event inspirited the desponding Americans, and nerved them for the contest soon to take place upon the main.

41 Major Leitch died on the first of October. Knowlton was carried to the redoubt, near the Hudson, at One hundred and Fifty-sixth Street, where he expired before sunset, and was buried within the embankments. His death was a public loss. His bravery at Bunker Hill commanded the highest respect of Washington. In general orders in the morning after the battle on Harlem Plains, the commander-in-chief, alluding to the death of Knowlton, said, "He would have been an honor to any country." |

September 20-21, 1776: The FIRE

RUINS OF TRINITY CHURCH

. The British strengthened MïGowanÍs Pass, placed strong pickets in advance of their lines, and guarded their flanks by armed vessels in the East and North Rivers. General Robertson, in the mean while, had taken possession of the city, and commenced strengthening the intrenchments across the island there. He had scarcely pitched his tents upon the hills in the present Seventh and Tenth Wards, and began to look with complacency upon the city as snug winter quarters for the army, when columns of lurid smoke rolled up from the lower end of the town. It was midnight [September 20-21, 1776.]. Soon broad arrows of flame shot up from the darkness, and a terrible conflagration began. 42 It was stayed by the exertions of the troops and sailors from the ships, but0 not until ab0out five hundred houses were consumed.

The British strengthened MïGowanÍs Pass, placed strong pickets in advance of their lines, and guarded their flanks by armed vessels in the East and North Rivers. General Robertson, in the mean while, had taken possession of the city, and commenced strengthening the intrenchments across the island there. He had scarcely pitched his tents upon the hills in the present Seventh and Tenth Wards, and began to look with complacency upon the city as snug winter quarters for the army, when columns of lurid smoke rolled up from the lower end of the town. It was midnight [September 20-21, 1776.]. Soon broad arrows of flame shot up from the darkness, and a terrible conflagration began. 42 It was stayed by the exertions of the troops and sailors from the ships, but0 not until ab0out five hundred houses were consumed.

The sketch of the ruins is from a picture made on the spot, and published in Dr. BerrianÍs History of Trinity Church.

Perceiving the Americans to be too strongly intrenched upon Harlem Heights to promise a successful attack upon them, Howe attempted to get in their rear, to cut off their communication with the north and east, and hem them in upon the narrow head of Manhattan Island.

WashingtonÍs Headquarters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert Murray |